Kanban and Game Development with Trello

☕☕☕ 14 min read

Context

Metidia, a start-up developing video games

I’m associate in a parisian start-up called Metidia.

Concretely, we build video games about consumer goods because we want to change the online selling world. Thus, we work on Vinoga: a Facebook social-farming game − think “FarmVille”, “Hay Day” − which is about wine. You are a winemaker, discovering the steps that will make you produce actual bottles across your journey. While your vines are growing you can even take a look at your wine list, customize, order and then enjoy for real the great vintages you have virtually produced.

Our challenge, as a start-up, is to iterate from an initial idea to a business model that works, before we get out of resources.

And there, among every roles you typically accumulate within a start-up, I’m the one responsible of the production part: ensure the team makes stuff happen, tests hypothesis and builds the game that will meet clients-players needs.

Our production team is composed from 1 Game Designer, 1 Game Artist and 2/3 Developers. Although we were 2 at the beginning, without much organization, we quickly had to adapt not to repeat mistakes of the early days − produced assets that become obsolete before being integrated ; poor code quality that should be reworked because of bugs…

We took advantage of our flexibility to adopt de facto the Agile principles. At the beginning, it was all trial and error. We learned a lot from Scrum to organize ourselves, but it reveals to be too heavy, not suited to our early needs and context.

At the end, I think that Agile is a buffet from which you should take the best.

We progressively composed a process that is adapted to us, pecking best practices that worked for us.

Finally, Kanban appeared to be particularly efficient for the team: flexible enough to continuously adapt ; still robust enough to avoid people disperse their energy around − which is not quite easy when you deal with creative minds.

Kanban, what is that?

To put it simply, Kanban is a “visual process-management system that tells what to produce, when to produce it, and how much to produce”.

The heart of Kanban is to visualise the production process to set up a limited pull system of work in progress. That means you limit the number of parallel tasks for each step of your process. Whenever there is a free space, the downstream step will take an upstream task - that’s the pull system - to make the work flow, not the other way.

Concretely, here’s how would look a typical Kanban process: One day in Kanban land

Moving to Kanban is dead easy since you start with what you’ve got:

- identify existing processes (eg: the production process, the player support process…)

- decompose workflows of every identified process

- setting limits to work in progress − simply start with what you’ve got

Then, the key is to progressively improve your flow with the team. This is Kaizen, an essential part of Kanban: the team regularly has a retrospective look to continuously and incrementally improve the way they work. This way, they can adapt themselves to the context, try new ideas, adapt to changes…

That’s the way we made Work In Progress (WIP) limits evolve for each process step, until we reach values that make us really productive - low WIP = high throughput − without being stuck… which is good for morale!

Big picture

We adopted Trello since the very beginning in 2013. Free, intuitive, easy onboarding, it is our virtual whiteboard and partner in crime which evolves along with our organization.

Trello boards are very flexible, which allows us to make changes through time regarding our needs.

Trello can also be used for remote teams, and it is much more than that. It’s whatever you need it to be, based on the projects you’re working on whether they are for different clients.

And so we may create and close diverse boards regarding projects we work on. These boards structure may vary regarding what’s needed: a temporary project managed with some GANTT because business needs it - thanks to the Elegantt extension ; a simple TODO > Doing > Done Kanban to handle a subproject ; etc.

All that aside, we have set up a board for each identified process:

- Production

- Business

- Support

- Communication

Each board represents a single activity that has its workflow.

In this post, I’ll just focus on the production board cogs.

The production board

The − Kanban − production board represents our production force, the work of the production team. This is valid, whatever should be produced: bug correction, new feature on Vinoga or another product, hotfix… Whatever should be delivered by the team.

This is an honest point of view of the work capacity of the team. That way we can prioritize everything we do and standardize the production process.

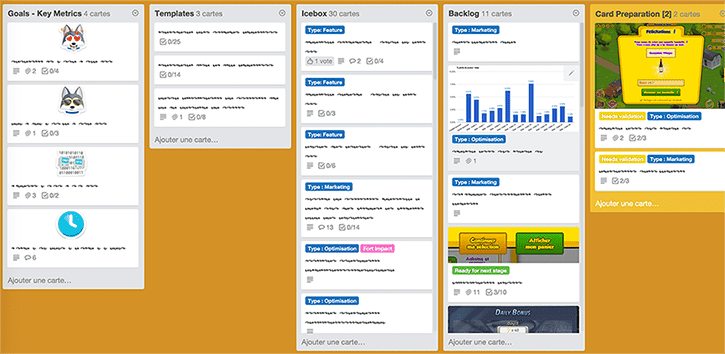

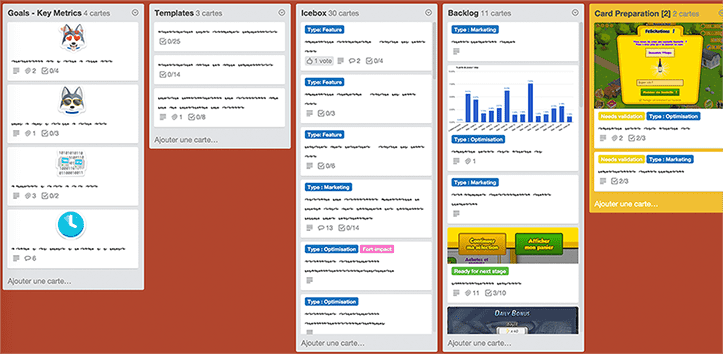

Goals

The very first list of the board contains our key metrics: the 3/4 KPIs that really matter for us. This is for the team to always keep an eye on them. That’s a source of motivation!

We review these every month to understand where we are and decide where do we go.

This is also an opportunity to celebrate successes together, because that’s good for morale!

Templates

This list is mostly an utility: it contains cards that are templates which save our time.

Actually, we don’t really use “card templates” as we want to keep the card creation process simple to anyone that may have an idea. As anyone can create a card, it’d be utopian to imagine they’d duplicate the appropriate card whenever it happens, because it’s not intuitive at all.

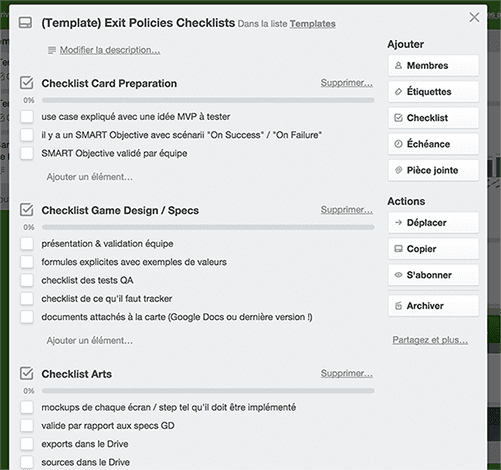

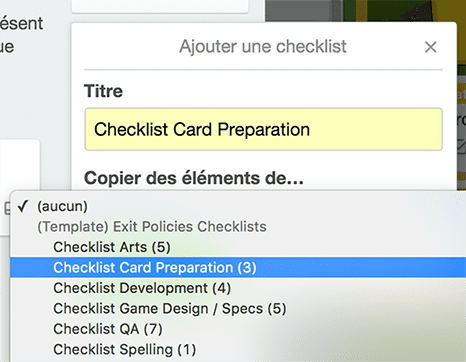

However, we use these cards to hold checklists templates.

Indeed, Kanban advocates to “make process policies explicit”: anyone should be able to know whether or not a card is ready to move to the next step of the flow. This is why the team has agreed on − and make evolve − exit policies for each step of the production flow. And the best way we found to make it work with Trello is using checklists!

Thus, when we’re done with some card, we know that we have to create the exit checklist. Which is made easy with templates:

Our trick to quickly retrieve your checklists templates is to name your card to have it appear at the top of the list.

The (Template) prefix is perfect for that.

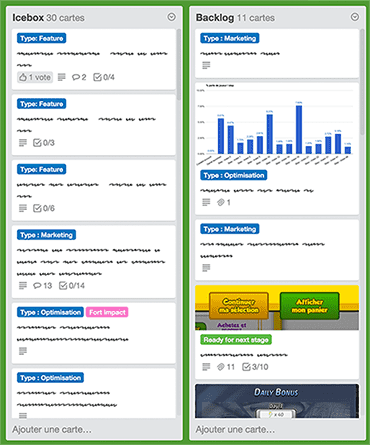

Icebox / Backlog

How to handle the “Backlog” is certainly what took us the most time to figure out: where should we put ideas, incoming TODOs, without it becomes a heavy mess to deal with?

We tested a lot of alternatives, including using a “Planning” board just like UserVoice did. But what really worked for us was to include a “Backlog” list, directly in the production board.

Cards in this list are prioritized, which means the team will treat the card which is on the top as soon as possible. That way we can re-prioritize cards until the very last moment.

That’s deferring decisions as late as possible to be more efficient.

We used to limit the size of the backlog to avoid cards to pile up faster than we would be able to treat them. But we finally drop that limitation since the team has become able to self-manage. Cumulative Flow Diagram is enough to make us visualize the current tendency at a glance and understand if we’re adding more cards than reasonable.

Therefore, “Backlog” contains cards we decided to handle soon. They generally are related to one of the main goals we are focusing on.

However, I dare you to make a creative team stop having ideas! And to support this creativity, you should break down barriers. This is why “Icebox” exists!

Without any card limitation, it holds any idea or suggestion that wouldn’t necessarily be part of the backlog (eg: ideas to improve game monetization while current focus is on retention).

We regularly check these cards to move to the backlog those which become relevant, delete those which are not applicable anymore or even add some info and ideas to others.

Keeping this list into the board makes things easy and flexible. It gives us a mid-long term vision. Still, we don’t spend that much time on it because you know, as a start-up, the mid-long term may rapidly change.

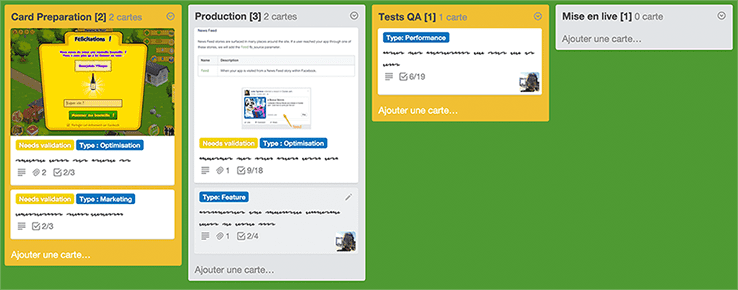

Production workflow

This concretely represents the different steps each card will pass through.

Each step has a WIP limit which is indicated in the list title.

Cards flow being “pulled”: whenever a step is completed, the card still there − with a little green label − until someone from the downstream step can take charge of it. All that, respecting WIP limits.

Exceptionally, some cards may not respect WIP limits. That may happen for an urgent one (eg: critical hotfix required in production) or a card waiting for some external dependency (eg: waiting for Facebook validation). In these cases, cards have an explicit red label. But these cases are rare.

Card Preparation

Cards are prepared for the rest of the flow.

That’s here we detail the card use case along with its SMART objective. Any card has an objective − why would it be there otherwise? Whether its a bug correction or a whole new feature, there should be a reason for us to deal with this card instead of another one. Furthermore, we determinate how we would be able to know if the objective is reached and what to do on success or failure.

Thus, we don’t lose that much time preparing cards that lie in the backlog. Only the main goal matters at that point. Then, we dig the idea into Card Preparation. We agree on the scope of the card or the way we split it into smaller ones − a game mechanics can generally be decomposed into smaller features we can implement one after the other.

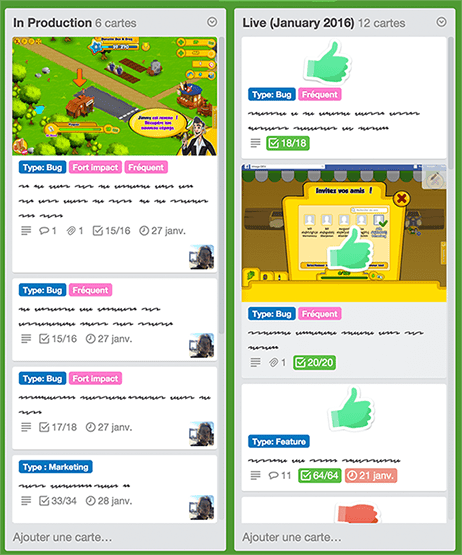

Production

Here will happen the game design / spelling / arts / development of a card.

Anyone is free to use checklists to organize its work. Even to create a temporary board if needed.

For a while, we use to detail every production step − specs, arts, dev… − with a list. However, that was not flexible enough, nor realistic.

A single “Production” list gives us more latitude so developers can directly work hand-to-hand with game artists during integration for instance ; or whenever no game artist is available for a week, preventing “air bubbles” into the flow.

QA Tests

There, we will ensure that what we produced matches what was expected. A pair usually deals with this part to ensure the quality − the game designer, someone from the business team, another developer that didn’t code…

We also make sure that we are able to answer the SMART objective we defined.

If anything goes wrong, the card lies there and block the rest of the flow until it’s fixed. Thus, the team will better getting things done before starting new stuff. That makes everyone cares about the quality.

Mise en live (= release)

This is the release part, where what has been produced goes to production.

We continuously deploy everything. If needed, we use feature flipping to activate / deactivate any feature.

Live

Once released into production, cards are not done yet.

Remember that any card has an associated SMART objective the team agreed on? Well, once in production, we do analyse it.

That can be done when the card is released − that’s the case with most of bug fixes − or later if we need to collect some data − A/B tests, for instance. In the latter case, we set a due date and a responsible to the card.

When the analysis is done, the card is considered completed. We move it into the Live of the current month. Then we follow the scenario we forecasted regarding if the objective was reached or not. Objectives can be considered as our “assumptions” within the meaning of Lean Startup.

We do a monthly review of cards that were put to live = what we learned.

Lessons learned & Anecdotes

Here is a loose couple of stuff we learned or set up and that revealed useful to us.

Keep it simple

Well, that’s all about the KISS principle. Keep it in mind, really.

For example, I realized that the more I created boards to distinguish works, having specific workflow for every board just like UserVoice did, the less it was efficient for the team. The truth is that what is essential should be kept under your eyes to keep focus.

Otherwise? It wouldn’t be easily adopted, nor actually used by the team… because that’s not practical for them. Don’t overengineer things more than absolutely needed.

Concerning cards estimations…

… that’s a waste of time for us.

There are plenty of debates on the subject, which I won’t detail here.

But, in our case, we now have an efficient and fast “production line”, thanks to Kanban. We know our average speed to produce something, thanks to indicators. We do our best to homogenize the size of incoming cards and continuously ship changes to our game, focusing on what matters.

If a card is really urgent, you just need to put it at the top of the backlog and it will naturally be shipped to production within a known, reliable and reasonable delay − 8 calendar days so far, in average.

If that’s even more urgent and that couldn’t wait, then a red label will make it skip the line and be handled in priority − that’s the fast-line. Still, this kind of emergency is quite rare once you’ve got a production team that can introduce change as best and quick as possible.

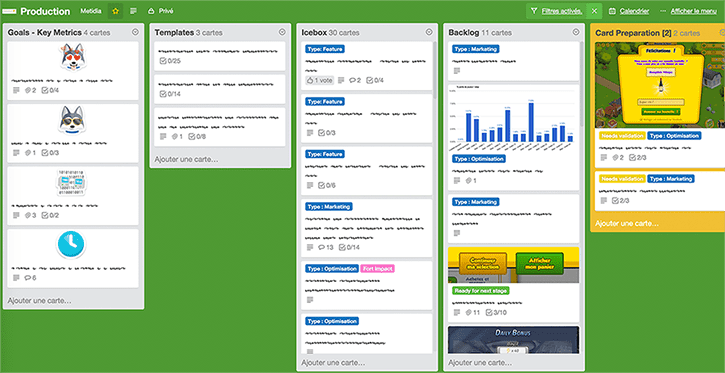

Visual management

“Visualize” is one of the central pillars of Kanban specifically, and among other Agile practices in general.

Trello perfectly fulfill that need with power-ups such as GitHub, or through its API.

For instance, we do change the background color of the board regarding the state of our continuous integration system.

When it’s green, everything goes fine!

When it’s orange, then a deployment is occurring:

Once deploy is completed, it turns back to green. But if it has failed to deploy, background turns to red so everyone knows:

Kanban & Trello visualisation

In order to know how much cards each list has, I do filter the board over * so I don’t actually hide any card.

With that said, I actually don’t know why the number of cards in a list only shows up when you’re filtering.

I also use a Chrome extension to give some color to lists background regarding the number of cards in it. If the WIP limit you set is reached, it becomes yellow. If the limit is exceeded, it turns red. This is not truly a must-have, but that’s really helpful to understand the state of the flow at a glance.

There seems to have a Chrome extension that does all of this: CardCounter for Trello, but since I didn’t tested it, I can’t recommend it.

Another very useful extension: Card color titles which displays labels titles right on the cards.

And then, Ollert which is a nice exhaustive visualisation tool. It can draw the Cumulative Flow Diagram for a defined period of your board, among other stuff.

Board “Calendar”

Let’s end this post with a story about a board we named “Calendar”.

It was here for a purpose: what do we do for a task that should be done at a specific date, not before, nor after? In other words, a task that simply can’t be put into the flow.

So we set up this basic TODO > Doing > Done board with the calendar power-up enabled. Each card was assigned to someone and a due date was set. Which was all we needed.

At the end, there were less and less cards of this kind as the team get trained with the Kanban mindset and the organization evolved to what it is today. Every use case that used to be “unique, which can’t work in a Kanban system” − there were often marketing / business tasks by the way − finally found its way into the flow as the Kanban philosophy was understood.

And, at last, I deleted this board that became useless… upon the team request!